Index :

Mesoamerica

Olmec

Zapotec

Teotihuacan

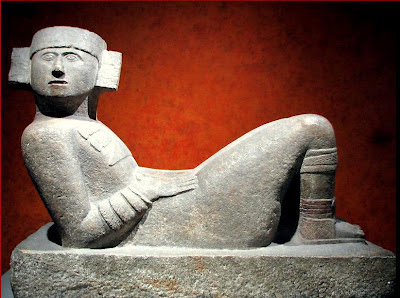

Toltec

Maya Civilization

Aztec

Mesoamerica (Spanish: Mesoamérica) is a region and cultural area in the Americas, extending approximately from central Mexico to Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica, within which a number of pre-Columbian societies flourished before the Spanish colonization of the Americas in the 15th and 16th centuries

As a cultural area, Mesoamerica is defined by a mosaic of cultural traits developed and shared by its indigenous cultures. Beginning as early as 7000 BC the domestication of maize, beans, squash and chili, as well as the turkey and dog (Their value in ancient native cultures is evidenced by their frequent appearance in art and artifacts, for example, those produced by the Colima, Aztec and Toltec civilizations in Mexico.

[Xolos were considered sacred dogs by the Aztecs (and also Toltecs, Maya and some other groups) because they believed the dogs were needed by their masters’ souls to help them safely through the underworld, and also they were useful companion animals.The Xolo dog is native to Mexico. Archaeological evidence shows that the breed has existed in Mexico for more than 3,000 years. When Columbus arrived in the Caribbean in 1492, his journal entries noted the presence of strange hairless dogs. Subsequently, Xolos were transported back to Europe

]

While Mesoamerican civilization did know of the wheel and basic metallurgy, neither of these technologies became culturally important.

Olmec

The Olmec flourished during Mesoamerica's Formative period, dating roughly from as early as 1500 BCE to about 400 BCE. They were the first Mesoamerican civilization and laid many of the foundations for the civilizations that followed. Among other "firsts", the Olmec appeared to practice ritual bloodletting and played the Mesoamerican ballgame, hallmarks of nearly all subsequent Mesoamerican societies.

The most familiar aspect of the Olmecs is their artwork, particularly the aptly named "colossal heads".The Olmec civilization was first defined through artifacts which collectors purchased on the pre-Columbian art market in the late 19th century and early 20th century. Olmec artworks are considered among ancient America's most striking. It is now generally accepted that these heads are portraits of rulers, perhaps dressed as ballplayers

Scholars have not determined the cause of the eventual extinction of the Olmec culture. Between 400 and 350 BCE, the population in the eastern half of the Olmec heartland dropped precipitously, and the area was sparsely inhabited until the 19th century. This depopulation was likely the result of "very serious environmental changes that rendered the region unsuited for large groups of farmers", in particular changes to the riverine environment that the Olmec depended upon for agriculture, hunting and gathering, and transportation.

The "Olmec heartland" is an archaeological term used to describe an area in the Gulf lowlands that is generally considered the birthplace of the Olmec culture. This area is characterized by swampy lowlands punctuated by low hills, ridges, and volcanoes.

What is today called Olmec first appeared fully within the city of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, where distinctive Olmec features occurred around 1400 BCE. The rise of civilization was assisted by the local ecology of well-watered alluvial soil, as well as by the transportation network provided by the Coatzacoalcos River basin. This environment may be compared to that of other ancient centers of civilization: the Nile, Indus, and Yellow River valleys, and Mesopotamia.

The first Olmec center, San Lorenzo, was all but abandoned around 900 BCE at about the same time that La Venta rose to prominence. A wholesale destruction of many San Lorenzo monuments also occurred circa 950 BCE, which may indicate an internal uprising or, less likely, an invasion. The latest thinking, however, is that environmental changes may have been responsible for this shift in Olmec centers, with certain important rivers changing course.

Scholars have not determined the cause of the eventual extinction of the Olmec culture. Between 400 and 350 BCE, the population in the eastern half of the Olmec heartland dropped precipitously, and the area was sparsely inhabited until the 19th century

In addition to making human and human-like subjects, Olmec artisans were adept at animal portrayals, for example, the fish vessel to the right or the bird vessel in the gallery below.

At the El Manatí site, disarticulated skulls and femurs, as well as the complete skeletons of newborn or unborn children, have been discovered amidst the other offerings, leading to speculation concerning infant sacrifice. Scholars have not determined how the infants met their deaths. Some authors have associated infant sacrifice with Olmec ritual art showing limp were-jaguar babies, most famously in La Venta's Altar 5 (on the right) or Las Limas figure.

Among other "firsts", the Olmec appeared to practice ritual bloodletting and played the Mesoamerican ballgame, hallmarks of nearly all subsequent Mesoamerican societies:

The Mesoamerican ballgame or o-llamaliztli (hispanized as Ulama) in Nahuatl was a sport with ritual associations played since 1,400 B.C. by the pre-Columbian peoples of Ancient Mexico and Central America. The sport had different versions in different places during the millennia, and a modern version of the game, ulama, is still played in a few places by the local indigenous population.

The rules of the ballgame are not known, but judging from its descendant, ulama, they were probably similar to racquetball, where the aim is to keep the ball in play. The stone ballcourt goals (see photo to right) are a late addition to the game.

In the most widespread version of the game, the players struck the ball with their hips, although some versions allowed the use of forearms, rackets, bats, or handstones. The ball was made of solid rubber and weighed as much as 4 kg (9 lbs), and sizes differed greatly over time or according to the version played.

The game had important ritual aspects, and major formal ballgames were held as ritual events, often featuring human sacrifice.

Games were played between two teams of players. The number of players per team could vary, between 2 to 4. Some games were played on makeshift courts for simple recreation while others were formal spectacles on huge stone ballcourts leading to human sacrifice.

Even without human sacrifice, the game could be brutal and there were often serious injuries inflicted by the solid, heavy ball. Today's hip-ulama players are "perpetually bruised" while nearly 500 years ago Spanish chronicler Diego Durán reported that some bruises were so severe that they had to be lanced open. He also reported that players were even killed when the ball "hit them in the mouth or the stomach or the intestines"

The ballgame was played within a large masonry structure. Built in a form that changed remarkably little during 2700 years, over 1300 Mesoamerican ballcourts have been identified, 60% in the last 20 years alone

The ballgame was a ritual deeply engrained in Mesoamerican cultures and served purposes beyond that of a mere sporting event. Fray Juan de Torquemada, a 16th century Spanish missionary and historian, tells that the Aztec emperor Axayacatl played Xihuitlemoc, the leader of Xochimilco, wagering his annual income against several Xochimilco chinampas.Ixtlilxochitl, a contemporary of Torquemada, relates that Topiltzin, the Toltec king, played against 3 rivals, the winner was to rule all

The association between human sacrifice and the ballgame appears rather late in the archaeological record, no earlier than the Classic era. The association was particularly strong within the Classic Veracruz and the Maya cultures, where the most explicit depictions of human sacrifice can be seen on the ballcourt panels – for example at El Tajin (850-1100 CE) and at Chichen Itza (900-1200 CE) – as well as on the well-known decapitated ballplayer stelae from the Classic Veracruz site of Aparicio (700-900 CE).

The Postclassic Maya religious and quasi-historical narrative, the Popol Vuh, also links human sacrifice with the ballgame

Captives were often shown in Maya art, and it is assumed that these captives were sacrificed after losing a rigged ritual ballgame. Rather than nearly nude and sometimes battered captives, however, the ballcourts at El Tajin and Chichen Itza show the sacrifice of practiced ballplayers, perhaps the captain of a team. Decapitation is particularly associated with the ballgame – severed heads are featured in much Late Classic ballgame art and appear repeatedly in the Popol Vuh. There has even been speculation that the heads and skulls were used as balls

For the Aztecs the playing of the ballgame also had religious significance, but where the 16th-century K´iche´ Maya saw the game as a battle between the lords of the underworld and their earthly adversaries

Zapotec

The Zapotec civilization was an indigenous pre-Columbian civilization that flourished in the Valley of Oaxaca of southern Mesoamerica.

The Zapotec state formed at Monte Albán began an expansion during the late Monte Alban 1 phase (400–100 BC) and throughout the Monte Alban 2 phase (100 BC – AD 200). Zapotec rulers began to seize control over the provinces outside the valley of Oaxaca. They could do this during Monte Alban 1c (roughly 200 BC) to Monte Alban 2 (200 BC – AD 100) because none of the surrounding provinces could compete with the valley of Oaxaca both politically and militarily. By 200 AD the Zapotecs had extended their influence, from Quiotepec in the north to Ocelotepec and Chiltepec in the south. Monte Albán had become the largest city in the southern Mexican highland, and so it remained until approximately 700 AD. The last battle between the Aztecs and the Zapotecs occurred between 1497 and 1502, under the Aztec ruler Ahuizotl. At the time of Spanish conquest of Mexico, when news arrived that the Aztecs were defeated by the Spaniards, King Cosijoeza ordered his people not to confront the Spaniards so they would avoid the same fate. They were defeated by the Spaniards only after several campaigns between 1522 and 1527. However, uprisings against colonial authorities occurred in 1550, 1560 and 1715.

Teotihuacan

Teotihuacan – also written Teotihuacán, with a Spanish orthographic accent on the last syllable – is an enormous archaeological site in the Basin of Mexico, just 30 miles (48 km) northeast of Mexico City, containing some of the largest pyramidal structures built in the pre-Columbian Americas. Apart from the pyramidal structures, Teotihuacan is also known for its large residential complexes, the Avenue of the Dead, and numerous colorful, well-preserved murals.

At its zenith, perhaps in the first half of the 1st millennium AD, Teotihuacan was the largest city in the pre-Columbian Americas, with a population of perhaps 125,000 or more, placing it among the largest cities of the world in this period. Teotihuacan began as a new religious center in the Mexican Highland around the first century AD. This city came to be the largest and most populated center in the New World. Teotihuacan was even home to multi-floor apartment compounds built to accommodate this large population. The early history of Teotihuacan is quite mysterious, and the origin of its founders is debated. For many years, archaeologists believed it was built by the Toltec. This belief was based on colonial period texts, such as the Florentine Codex, which attributed the site to the Toltecs. Since Toltec civilization flourished centuries after Teotihuacan, the people could not have been the city's founders.

The builders of Teotihuacan took advantage of the geography in the Basin of Mexico. From the swampy ground, they constructed raised beds, called chinampas. This allowed for the formation of channels, and subsequently canoe traffic to transport food from farms around the city.The earliest buildings at Teotihuacan date to about 200 BC. The largest pyramid, the Pyramid of the Sun, was completed by 100 AD

The earliest buildings at Teotihuacan date to about 200 BC. The largest pyramid, the Pyramid of the Sun, was completed by 100 AD

Scholars had thought that invaders attacked the city in the 7th or 8th century, sacking and burning it. More recent evidence, however, seems to indicate that the burning was limited to the structures and dwellings associated primarily with the elite class. Some think this suggests that the burning was from an internal uprising.

The decline of Teotihuacan has been correlated to lengthy droughts related to the climate changes of 535-536 AD. This theory of ecological decline is supported by archaeological remains that show a rise in the percentage of juvenile skeletons with evidence of malnutrition during the 6th century.

The sudden destruction of Teotihuacan is turning out to be more typical of Mesoamerican city-states than once thought. Many Maya states would suffer similar fates in the coming centuries. Near by in the highlands, Xochicacolo would be sacked and burned in 900 CE and Tula would meet a similar fate around 1150 CE.

Archaeological evidence suggests that Teotihuacan was a multi-ethnic city, with distinct quarters occupied by Otomi, Zapotec, Mixtec, Maya and Nahua peoples. The Totonacs have always maintained that they were the ones who built it. The Aztecs repeated that story, but it has not been corroborated by archaeological findings

Teotihuacanos practiced human sacrifice: human bodies and animal sacrifices have been found during excavations of the pyramids at Teotihuacan. Scholars believe that the people offered human sacrifices as part of a dedication when buildings were expanded or constructed. The victims were probably enemy warriors captured in battle and brought to the city for ritual sacrifice to ensure the city could prosper. Some men were decapitated, some had their hearts removed, others were killed by being hit several times over the head, and some were buried alive. Animals that were considered sacred and represented mythical powers and military were also buried alive, imprisoned in cages: cougars, a wolf, eagles, a falcon, an owl, and even venomous snakes.

Knowledge of the huge ruins of Teotihuacan was never completely lost. After the fall of the city, various squatters lived on the site. During Aztec times, the city was a place of pilgrimage and identified with the myth of Tollan, the place where the sun was created. Teotihuacan astonished the Spanish conquistadores during the post-conquest era.

The city's broad central avenue, called "Avenue of the Dead" (a translation from its Nahuatl name Miccoatli), is flanked by impressive ceremonial architecture, including the immense Pyramid of the Sun (Third largest in the New World after the Great Pyramid of Cholula) and the Pyramid of the Moon.

Further down the Avenue of the Dead is the area known as the Citadel, containing the ruined Temple of the Feathered Serpent. This area was a large plaza surrounded by temples that formed the religious and political center of the city. The name "Citadel" was given to it by the Spanish, who believed it was a fort. Most of the common people lived in large apartment buildings spread across the city.

The city-state of Teotihuacan dominated the Valley of Mexico until the early eight century, but we know little of the political structure of the region because the Teotihuacaners left no written records.

Toltec

The Toltec culture is an archaeological Mesoamerican culture that dominated a state centered in Tula, Hidalgo, in the early post-classic period of Mesoamerican chronology (ca 800-1000 CE). The later Aztec culture saw the Toltecs as their intellectual and cultural predecessors and described Toltec culture emanating from Tollan (Nahuatl for Tula) as the epitome of civilization, indeed in the Nahuatl language the word "Toltec" came to take on the meaning "artisan". The Aztec oral and pictographic tradition also described the history of the Toltec empire giving lists of rulers and their exploits.

While the skeptical school of thought does not deny that cultural traits of a seemingly central Mexican origin have diffused into a larger area of Mesoamerica, it tends to ascribe this to the dominance of Teotihuacán in the Classic period and the general diffusion of cultural traits within the region. Recent scholarship, then, does not see Tula, Hidalgo as the capital of the Toltecs of the Aztec accounts, but rather takes "Toltec" to mean simply an inhabitant of Tula during its apogee. Separating the term "Toltec" from those of the Aztec accounts, it attempts to find archaeological clues to the ethnicity, history and social organization of the inhabitants of Tula.

Other controversy relating to the Toltecs include how best to understand reasons behind the perceived similarities in architecture and iconography between the archaeological site of Tula and the Maya site of Chichén Itzá - as of yet no consensus has emerged about the degree or direction of influence between the two sites. Tula was city was the largest in central Mexico in the 9th and 10th centuries, covering an area of some 12 km² with a population of at least some 30,000, possibly significantly more. While it might have been the largest city in Mesoamerica at the time, some Maya sites in the Yucatán may have rivaled its population during this period. However Tula never grew to the size of Teotihuacan.

Preclassic Maya (1850 BC - 250 AD)

Classic period (250–900 AD)

During this period the Mayas numbered in the millions, they created a multitude of kingdoms and small empires, built monumental palaces and temples, engaged in grandiose ceremonies, and developed an elaborate hieroglyphic writing system.

The Late Classic period (beginning ca. AD 600 until AD 909) is characterized as a period of interregional competition and factionalization among the numerous regional polities in the Maya area. This largely resulted from the decrease in Tikal’s socio-political and economic power at the beginning. It was during this time that a number of other sites, therefore, rose to regional prominence and were able to exert greater interregional influence, including Caracol, Copán, Palenque, and Calakmul (who was allied with Caracol and may have assisted in the defeat of Tikal), and Dos Pilas Aguateca and Cancuén in the Petexbatún region of Guatemala. Around 710 DC, Tikal arose again and started to build strong alliances and defeated its worst enemies. In the Maya area, the Late Classic ended with the so-called Maya "collapse", a transitional period coupling the general depopulation of the southern lowlands and development and florescence of centers in the northern lowlands.

Generally applied to the Maya area, the Terminal Classic roughly spans the time between AD 800/850 and ca. AD 1000. Overall, it generally correlates with the rise to prominence of Puuc settlements in the northern Maya lowlands, so named after the hills in which they are mainly found. Puuc settlements are specifically associated with a unique architectural style (the "Puuc architectural style") that represents a technological departure from previous construction techniques. Chichén Itzá was originally thought to have been a Postclassic site in the northern Maya lowlands. Research over the past few decades has established that it was first settled during the Early/Late Classic transition but rose to prominence during the Terminal Classic and Early Postclassic. During its apogee, this widely known site economically and politically dominated the northern lowlands.

Collapse of the Clasic Maya:

The Maya centers of the southern lowlands went into decline during the 8th and 9th centuries and were abandoned shortly thereafter. This decline was coupled with a cessation of monumental inscriptions and large-scale architectural construction. The Classic Maya Collapse is one of the biggest mysteries in archaeology. What makes this development so intriguing is the combination of the cultural sophistication attained by the Maya before the collapse and the relative suddenness of the collapse itself

Some 88 different theories or variations of theories attempting to explain the Classic Maya Collapse have been identified. From climate change to deforestation to lack of action by Mayan kings, there is no universally accepted collapse theory, although drought is gaining momentum as the leading explanation. The colonial Spanish officials accurately documented cycles of drought, famine, disease, and war, providing a reliable historical record of the basic drought pattern in the Maya region.

The Maya succeeded in creating a civilization in a seasonal desert by creating a system of water storage and management which was totally dependent on consistent rainfall. The constant need for water kept the Maya on the edge of survival. “Given this precarious balance of wet and dry conditions, even a slight shift in the distribution of annual precipitation can have serious consequences.

During the succeeding Postclassic period (from the 10th to the early 16th century), development in the northern centers persisted, characterized by an increasing diversity of external influences. The Maya cities of the northern lowlands in Yucatán continued to flourish for centuries more; some of the important sites in this era were Chichen Itza, Uxmal, Edzná, and Coba. After the decline of the ruling dynasties of Chichen and Uxmal, Mayapan ruled all of Yucatán until a revolt in 1450. (This city's name may be the source of the word "Maya", which had a more geographically restricted meaning in Yucatec and colonial Spanish and only grew to its current meaning in the 19th and 20th centuries).

Colonial period

Unlike the Aztec and Inca Empires, there was no single Maya political center that, once overthrown, would hasten the end of collective resistance from the indigenous peoples. Instead, the conquistador forces needed to subdue the numerous independent Maya polities almost one by one, many of which kept up a fierce resistance. Most of the conquistadors were motivated by the prospects of the great wealth to be had from the seizure of precious metal resources such as gold or silver; however, the Maya lands themselves were poor in these resources. This would become another factor in forestalling Spanish designs of conquest, as they instead were initially attracted to the reports of great riches in central Mexico or Peru.

First Spanish accidental landing in Yucatán Peninsula

The first known Spanish landing on the Yucatán Peninsula was a product of misfortune, when in 1511 a small vessel bound for the island of Santo Domingo from Darién, Panama ran aground on some shoals in the Caribbean Sea, south of the island of Jamaica. The ship's complement of fifteen men and two women set off in the ship's boat in an attempt to reach Cuba or one of the other colonies. However, the prevailing currents forced them westwards until, after approximately two weeks of drifting, they reached the eastern shoreline of the Peninsula, possibly in present-day Belize. Captured by the local Maya, they were divided up among several of the chieftains as slaves and a number were sacrificed and killed according to offeratory practices. Over the succeeding years their numbers dwindled further as others were lost to disease or exhaustion, until only two were left– Gerónimo de Aguilar who had escaped his former captor and found refuge with another Maya ruler, and Gonzalo Guerrero who had won some prestige among the Maya for his bravery and had now the standing of a ranking warrior and noble. These two would later have notable, but very different, roles to play in future conflicts between the Spanish and the Mesoamerican peoples– Aguilar would become Hernan Cortés's translator and advisor, with Guerrero instead electing to remain with the Maya and served as a tactician and warrior fighting with them against the Spanish.

Friar Diego de Landa described the incident on his 'Account of Things of Yucatan' (see more below for reference for this book) as it follows:

"Que los primeros españoles que llegaron a Yucatán, según se dice, fueron Gerónimo de Aguilar, natural de Ecija, y sus compañeros, los cuales, el año de 1511, en el desbarato del Darien por las revueltas entre Diego de Nicuesa y Vasco Núñez de Balboa, siguieron a Valdivia que venía en una carabela a Santo Domingo, a dar cuenta al Almirante y al Gobernador de lo que pasaba, y a traer 20 mil ducados del rey; y que esta carabela, llegando a Jamaica, dio en los bajos que llaman de Vívores donde se perdió, no escapando sino 20 hombres que con Valdivia entraron en un batel sin velas y con unos ruines remos y sin mantenimiento alguno anduvieron trece días por el mar. Después de muertos de hambre casi la mitad, llegaron a la costa de Yucatán, a una provincía que llaman de la Maya...

... Que esta pobre gente vino a manos de un mal cacique, el cual sacrificó a Valdivia y a otros cuatro a sus ídolos y después hizo banquetes (con la carne) de ellos a la gente, y que dejó para engordar a Aguilar y a Guerrero y a otros cinco o seis, los cuales quebrantaron la prisión y huyeron por unos montes. Y que aportaron a otro señor enemigo del primero y más piadoso, el cual se sirvió de ellos como de esclavos; y que el que sucedió a este señor los trató con buena gracia, pero que ellos, de dolencia, murieron quedando solos Gerónimo de Aguilar y Gonzalo Guerrero, de los cuales Aguilar era buen cristiano y tenía unas horas por las cuales sabía las fiestas. Y que éste se salvó con la ida del marqués Hernando Cortés, el año de 1519, y que Guerrero, como entendía la lengua, se fue a Chectemal (Chactemal), que es la Salamanca de Yucatán, y que allí le recibió un señor llamado Nachancán (Ah Na Chan Can), el cual le dio a cargo las cosas de la guerra en que (est)uvo muy bien, venciendo muchas veces a los enemigos de su señor, y que enseñó a los indios pelear mostrándoles (la manera de) hacer fuertes y bastiones, y que con esto y con tratarse como indio, ganó mucha reputación y le casaron con una muy principal mujer en que hubo hijos; y que por esto nunca procuró salvarse como hizo Aguilar, antes bien labraba su cuerpo, criaba cabello y harpaba las orejas para traer zarcillos como los indios y es creible que fuese idólatra como ellos."

1517 Expedition and Discovery of the Yucatan

Together with some 110 discontented Spanish settlers in early colonial Cuba, Hernández de Córdoba petitioned the governor, Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, for permission to launch an expedition in search of new lands and exploitable resources. This permission was granted after some haggling over terms, and the expedition consisting of three ships under Hernández de Córdoba's command left the harbor of Santiago de Cuba on February 8, 1517, to explore the shores of southern Mexico. The main pilot was Antón de Alaminos, the premiere navigator of the region who had accompanied Christopher Columbus on his initial voyages.

Later they had 21 days of fair weather and calm seas after which they spotted land and, quite near the coast and visible from the ships, the first large populated center seen by Europeans in the Americas, with the first solidly built buildings. The Spaniards, who evoked the Muslims in all that was developed but not Christian, spoke of this first city they discovered in America as El gran Cairo, as they later were to refer to pyramids or other religious buildings as mezquitas, "mosques".

These contacts of March 4 may have been the birth of the toponyms Yucatán and Catoche, whose surprising and amusing history — perhaps too amusing to be true — is often cited. Be it history or legend, the story is that the Spaniards asked the Indians for the name of the land they had just discovered and on hearing the predictable replies to the effect of "I don't understand what you said", "those are our houses" gave the land names based on what they had heard: Yucatán, meaning "I don't understand you" for the whole "province" (or island, as they thought), and Catoche, meaning "our houses", for the settlement and the cape where they had debarked.

The Spaniards' fears were almost immediately confirmed. The chief had prepared an ambush for the Spaniards as they approached the town. They were attacked by a multitude of Indians, armed with pikes, bucklers, slings. The Spanish soon learned that the Mayan arrows, while not attaining any distinct force behind them, tended to shatter on impact leading to a slow and painful death. In this days two Indians were captured, taken back on board the Spanish ships. These individuals, who once baptized into the Roman Catholic faith received the names Julianillo and Melchorejo (anglicized, Julián and Melchior), would later became the first Maya language interpreters for the Spanish, on Grijalva's subsequent expedition.

Fifteen days after Catoche, the expedition landed to fill their water vessels near a Maya village they called Lázaro (after St Lazarus' Sunday, the day of their landing; "The proper Indian name for it is Campeche", clarifies Bernal). Once again they were approached by Indians appearing to be peaceable, and the now-suspicious Spaniards maintained a heavy guard on their disembarked forces. During an uneasy meeting, the local Indians repeated a word (according to Bernal) that ought to have been enigmatic to the Spaniards: "Castilian". This curious incident of the Indians apparently knowing the Spaniards' own word for themselves they later attributed the presence of the shipwrecked voyagers of de Nicuesa's unfortunate 1511 fleet. Unbeknownst to de Córdoba's men, the two remaining survivors, Jerónimo de Aguilar and Gonzalo Guerrero, were living only several days' walk from the present site.

The Spaniards found a solidly-built well used by the Indians to provide themselves with fresh water and they could fill their casks and jugs. The Indians, again with friendly aspect and manner, brought them to their village, where once more they could see solid constructions and many idols (Bernal alludes to the busts of serpents on the walls, so characteristic of Mesoamerica). They also met their first priests, with their white tunics and their long hair impregnated with human blood; this was the end of the Indians' friendly conduct: they convoked a great number of warriors and ordered them to burn some dry reeds, indicating to the Spaniards that if they weren't gone before the fire went out, they would be attacked. Hernández's men decided to retreat to the boats with their casks and jugs of water before the Indians could attack them, leaving safely behind them the discovery of Campeche.

Champotón battle: They sailed some six days in good weather and another four in a tempest that almost wrecked their ships. Their supply of good drinking water was now yet again exhausted, owing to the poor condition of the containers. Being now in an extreme situation, they stopped to gather water in a place that Bernal sometimes calls Potonchán and sometimes by its present-day name of Champotón, where the river of the same name meets the sea. When they had filled the jugs, they found themselves surrounded by great assemblies of Indians. They passed the night on land, with great precautions and wakeful vigilance.

When dawn broke, they were evidently vastly outnumbered ("by two hundred to one", claims Bernal), and only shortly into the ensuing battle Bernal speaks of eighty injured Spaniards. Keeping in mind that the original number of the expedition was about a hundred, not all soldiers, this suggests that at that moment the expedition was close to destruction. They soon discovered that the legions of Indians were being continually replenished by fresh reinforcements, and if good swords, crossbows, and muskets had astonished them at first, they had now overcome the surprise and maintained a certain distance from the Spaniards. At the cry of "Calachumi", which the conquistadors soon learned was a word for "chief" or "captain", the Indians were particularly merciless in attacking Hernández de Córdoba, who was hit by ten arrows. The Spanish also learned the dedication of their opponents to capturing people alive: two were taken prisoner and certainly sacrificed afterwards; of one we know that his name was Alonso Boto, and of the other Bernal is only able to say of him that he was "an old Portuguese".

Eventually, with only one Spanish soldier remaining unhurt, the captain practically unconscious, and the aggression of the Indians only increasing, they decided then that their only recourse was to form a close phalanx and break out of their encirclement in the direction of the launches, and to return to board them. The Spaniards had lost fifty companions, including two who were taken alive. The survivors were badly injured, with the sole exception of a soldier named Berrio, who was surprisingly unscathed. Five died in the following days, the bodies were buried at sea.

The expeditionaries had returned to the ships without the fresh water that had been the original reason to land. Furthermore, they saw their crew reduced by more than fifty men, many of them sailors, which combined with the great number of the seriously injured made it an impossibility to operate three ships. The thirst began to become intolerable. Bernal writes that their tongues and throats cracked, and of soldiers who were driven by desperation to drink sea water. Another land excursion of fifteen men, in a place which they called Estero de los Lagartos, "Lizards' Estuary", obtained only brackish water which increased the desperation of the crew. In the event, the twenty people — among them, Bernal and the pilot Alaminos — who debarked in search of water were attacked by natives, although this time they came out victorious, with Bernal nonetheless receiving his third injury of the voyage, and Alaminos taking an arrow in the neck. One of the sentries who had been placed on guard around the troop disappeared: Berrio, precisely the only soldier who had escaped unscathed in Champotón. Now with fresh water, they headed to Havana in the two remaining ships, and not without difficulties. Francisco Hernández de Córdoba barely reached Cuba; suffering from his mortal wounds, he expired within days of reaching the port, along with three other sailors.

The discovery of El Gran Cairo, in March 1517 encouraged two further expeditions: the first in 1518 under the command of Juan de Grijalva and the second in 1519 under Hernán Cortes commandment. Diego Velázquez, the governor of Cuba, ordered an expedition sent out with four ships supplied with crossbows, muskets, salt pork, and cassava bread for some 240 men led by his nephew, Juan de Grijalva. This expedition obtained similar results as the Cordoba's expedition and he was disappointed at gathering very little gold, but came back to Cuba with a tale that a rich empire was further to the west. The news that this "island" of Yucatán had gold, doubted by Bernal but enthusiastically maintained by Julianillo, the Maya prisoner taken at the battle of Catoche, fed the subsequent series of events that was to end with the Conquest of Mexico by the third flotilla sent, that of Hernán Cortés.

Hernan Cortés Expedition in Yucatan

:

Cortés was Born in Medellín (Extremadura) Spain, to a family of lesser nobility, Cortés chose to pursue a livelihood in the New World.

Through his mother, Hernán was the second cousin once removed of Francisco Pizarro, who later conquered the Inca Empire of modern-day Peru.

At the age of 14, Cortés was sent to study at the University of Salamanca in west-central Spain. This was Spain's great center of learning, and while accounts vary as to the nature of Cortés's studies, his later writings and actions suggest he studied Law and probably Latin.

Being 18 years old he finally left for Hispaniola in 1504 where he became a colonist: Upon his arrival in 1504 in Santo Domingo, the capital of Hispaniola, the 18-year-old Cortés registered as a citizen, which entitled him to a building plot and land to farm. Soon afterwards, Nicolás de Ovando, still the governor, gave him a encomienda and made him a notary of the town of Azua de Compostela. His next five years seemed to help establish him in the colony; in 1506, Cortés took part in the conquest of Hispaniola, receiving a large estate of land and Indian slaves for his efforts from the leader of the expedition. In 1511, Cortés accompanied Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, an aide of the Governor of Hispaniola, in his expedition to conquer Cuba. Velázquez was appointed as governor. At the age of 26, Cortés was made clerk to the treasurer with the responsibility of ensuring that the Crown received the quinto, or customary one-fifth of the profits from the expedition. The Governor of Cuba, Diego Velázquez, was so impressed with Cortés that he secured a high political position for him in the colony. He became secretary for Governor Velázquez. Cortés was twice appointed municipal magistrate (alcalde) of Santiago. In Cuba, Cortés became a man of substance with a encomienda to provide Indian labor for his mines and cattle. This new position of power also made him the new source of leadership, which opposing forces in the colony could then turn to. It was not until he had been almost 15 years in the Indies, that Cortés began to look beyond his substantial status as mayor of the capital of Cuba and as a man of affairs in the thriving colony. He missed the first two expeditions, under the orders of Francisco Hernández de Córdoba and then Juan de Grijalva, sent by Diego Velázquez to Mexico in 1518.

In 1518 Gobernor of Cuba Diego Velázquez put Cortés in command of an expedition to explore and secure the interior of Mexico for colonization. At the last minute, due to the old gripe between Velázquez and Cortés, he changed his mind and revoked his charter. Cortés ignored the orders and went ahead anyway, in February 1519, in an act of open mutiny.

Cortés landed at Cozumel and spent some time there, trying to convert the locals to Christianity and achieving mixed results. While at Cozumel, Cortés heard reports of other white men living in the Yucatán. Cortés sent messengers to these reported castilianos, who turned out to be the survivors of a Spanish shipwreck that had occurred in 1511.

On arriving in the island of Cozumel from Cuba, Cortés sent a letter by Maya messenger across to the mainland, inviting the two Spaniards, of whom he'd heard rumors, to join him. Aguilar became a translator, during the Conquest. According to the account of Bernal Díaz, when the newly freed friar attempted to convince Guerrero to join him, Gonzalo Guerrero responded:

Spanish: "Hermano Aguilar, yo soy casado y tengo tres hijos. Tienenme por cacique y capitán, cuando hay guerras, la cara tengo labrada, y horadadas las orejas. ¿Que dirán de mi esos españoles, si me ven ir de este modo? Idos vos con la bendición de Dios, que ya veis que estos mis hijitos son bonitos, y dadme por vida vuestra de esas cuentas verdes que traeis, para darles, y diré, que mis hermanos me las envían de mi tierra."

English Translation: "Brother Aguilar; I am married and have three children, and they look on me as a cacique (lord) here, and captain in time of war. My face is tattooed and my ears are pierced. What would the Spaniards say about me if they saw me like this? Go and God's blessing be with you, for you have seen how handsome these children of mine are. Please give me some of those beads you have brought to give to them and I will tell them that my brothers have sent them from my own country."

Díaz goes on to describe how Gonzalo's Mayan wife Zazil Há interrupted the conversation and angrily addressed Aguilar in her own language:

Spanish: " Y asimismo la india mujer del Gonzalo habló a Aguilar en su lengua, muy enojada y le dijo: Mira con qué viene este esclavo a llamar a mi marido: idos vos y no curéis de más pláticas."

English Translation: "And the Indian wife of Gonzalo spoke to Aguilar in her own tongue very angrily and said to him, "What is this slave coming here for talking to my husband, - go off with you, and don't trouble us with any more words.""

Then Aguilar spoke to Guerrero again, reminding him that he was of Christian faith and should not throw away his everlasting soul for the sake of an Indian woman. But Gonzalo was not to be convinced.

Aguilar, now quite fluent in Yucatec Maya as well as some other indigenous languages, would prove to be a valuable asset for Cortés as a translator, a skill of particular significance to the later conquest of the Aztec Empire which would be the end result of Cortés' expedition. Although Guerrero's later fate is uncertain, it appears that for some years he continued to fight alongside the Maya forces against Spanish incursions, providing military counsel and encouraging resistance; he quite possibly was killed in a later battle.

In March 1519, Cortés formally claimed the land for the Spanish crown. He stopped in Trinidad to hire more soldiers and obtain more horses. Then he proceeded to Potonchan, Tabasco, where he met with resistance and won a battle against the natives. He received twenty young indigenous women from the vanquished natives and he converted them all to Christianity. Among these women was La Malinche, his future mistress and mother of his child Martín. Malinche knew both the (Aztec) Nahuatl language and Maya, thus enabling Hernán Cortés to communicate in both. She became a very valuable interpreter and counselor.

Through her help, Cortés learned from the Tabascans about the wealthy Aztec Empire and its riches. Christened Marina by Cortés, she later learned Spanish, became Cortés' mistress and bore him a son. Bernal Díaz del Castillo wrote in his account The True History of the Conquest of New Spain that Doña Marina was "an Aztec princess sold into Mayan slavery." She was not actually an Aztec princess but was of noble birth, probably of Toltec or Tabascan origins.Native speakers of Nahuatl, her own people, would call her "Malintzin." This name is the closest phonetic approximation possible in Nahuatl to the sound of 'Marina' in Spanish. Over time, "la Malinche" (the modern Spanish cognate of 'Malintzin') became a term that denotes a traitor to one's people. To this day, the word malinchista is used by Mexicans to denote one who apes the language and customs of another country. Cortés then landed his expedition force on the coast of the modern day state of Veracruz with the purpose of conquering the Aztec empire...

Conquest of Yucatan

The richer lands of central Mexico engaged the main attention of the Conquistadors for some years, then in 1526 Francisco de Montejo (a veteran of the Grijalva and Cortés expeditions) successfully petitioned the King of Spain for the right to conquer Yucatán. He arrived in eastern Yucatán in 1527. The Spanish set up a small fort on the coast at Xamanha in 1528, but had no further success in subduing the country. Montejo went to Mexico to gather a larger army. Montejo returned in 1531 with a force that allied with the Maya port city of Campeche. While he set up a fortress at Campeche, he sent his son Francisco Montejo the Younger inland with an army. The leaders of some Maya states pledged that they would be his allies. He continued on to Chichen Itza, which he declared his Royal capital of Spanish Yucatán, but after a few months the locals rose up against him, the Spaniards were constantly attacked, and the Spanish force fled to Honduras. It was rumored that Gonzalo Guerrero, a Spaniard shipwrecked in 1511 who chose to stay in Yucatán, was among those directing Maya resistance to the Spanish crown. Montejo the Elder, who was now in his late 60s, turned his royal rights in Yucatán over to his son, Francisco Montejo the Younger. The younger Montejo invaded Yucatán with a large force in 1540. In 1542, he set up his capital in the Maya city of T'ho, which he renamed Mérida.

The lord of the Tutal Xiu of Maní converted to Christianity. The Xiu dominated most of Western Yucatán and became valuable allies of the Spanish, greatly assisting in the conquest of the rest of the peninsula. A number of Maya states at first pledged loyalty to Spain, but revolted after feeling the heavy hand of Spanish rule. Fighting and revolts continued for years. When the Spanish and Xiu defeated an army of the combined forces of the states of Eastern Yucatán in 1546, the conquest was officially complete; however, periodic revolts, which would be violently put down by Spanish troops and Indian auxiliaries, continued throughout the Spanish colonial era.

Conquest of the Maya highlands (current Guatemala)

After the Aztec empire fell to the Spanish in 1521, the Kaqchikel Maya of Iximche sent envoys to Hernán Cortés to declare their allegiance to the new ruler of Mexico, and the K'iche' Maya of Q'umarkaj may also have sent a delegation. In 1522 Cortés sent Mexican allies to scout the Soconusco region of lowland Chiapas, where they met new delegations from Iximche and Q'umarkaj at Tuxpán; both of the powerful highland Maya kingdoms declared their loyalty to the king of Spain. But Cortés' allies in Soconusco soon informed him that the K'iche' and the Kaqchikel were not loyal, and were instead harassing Spain's allies in the region. Cortés decided to despatch Pedro de Alvarado with 180 cavalry, 300 infantry, crossbows, muskets, 4 cannons, large amounts of ammunition and gunpowder, and hundreds of allied Mexican warriors from Tlaxcala and Cholula; they arrived in Soconusco in 1523.

On 12 February 1524 Alvarado's Mexican allies were ambushed in the pass and driven back by K'iche' warriors but the Spanish cavalry charge that followed was a shock for the K'iche', who had never before seen horses. The cavalry scattered the K'iche' and the army crossed to the city of Xelaju (modern Quetzaltenango) only to find it deserted. Although the common view is that the K'iche' prince Tecun Uman died in the later battle near Olintepeque, the Spanish accounts are clear that at least one and possibly two of the lords of Q'umarkaj died in the fierce battles upon the initial approach to Quetzaltenango. The legends say Tecún Umán entered battle adorned with precious quetzal feathers, and his nahual (animal spirit guide), also a quetzal bird, accompanied him during the battle. In the midst of the fray, both Alvarado and Tecún, warriors from worlds apart, met face to face, each with weapon in hand. Alvarado was clad in armor and mounted on his warhorse. As horses were not native to the Americas and peoples of Mesoamerica had no beasts of burden of their own, Tecún Umán assumed they were one being and killed Alvarado's horse.

Tecún Umán was declared a National Hero of Guatemala on March 22, 1960 and is celebrated annually on February 20. Tecún Umán's namesakes include a small town in the department of San Marcos on the Guatemala-Mexico border as well as countless hotels, restaurants, and Spanish schools throughout Guatemala. He is also memorialized in a poem by Miguel Ángel Asturias that bears his name.In contrast to his popularity, he is at times rejected by Maya cultural activists who consider his status as a national hero a source of irony, considering the long history of mistreatment of Guatemala's native population.

Almost a week later, on 18 February 1524,a K'iche' army confronted the Spanish army in the Quetzaltenango valley and were comprehensively defeated; many K'iche' nobles were among the dead. This battle exhausted the K'iche' militarily and they asked for peace and offered tribute, inviting Pedro de Alvarado into their capital Q'umarkaj, which was known as Tecpan Utatlan. He encamped on the plain outside the city rather than accepting lodgings inside. Fearing the great number of K'iche' warriors gathered outside the city and that his cavalry would not be able to maneouvre in the narrow streets of Q'umarkaj, he invited the leading lords of the city, Oxib-Keh (the ajpop, or king) and Beleheb-Tzy (the ajpop k'amha, or king elect) to visit him in his camp. As soon as they did so, he seized them and kept them as prisoners in his camp. The K'iche' warriors, seeing their lords taken prisoner, attacked the Spaniards' indigenous allies and managed to kill one of the Spanish soldiers.At this point Alvarado decided to have the captured K'iche' lords burnt to death, and then proceeded to burn the entire city.The Conquistadores have made alliance with thei Kaqchikel who had long been beitter rivals of the K`iche' . However, Pedro de Alvarado rapidly began to demand gold in tribute from the Kaqchikels, souring the friendship between the two peoples. He demanded that their kings deliver 1000 gold leaves, each worth 15 pesos. A Kaqchikel priest foretold that the Kaqchikel gods would destroy the Spanish—as a result the Kaqchikel people abandoned their city and fled to the forests and hills on 28 August 1524 (7 Ahmak in the Kaqchikel calendar). Ten days later the Spanish declared war on the Kaqchikel. Two years later, on 9 February 1526, a group of sixteen Spanish deserters burnt the palace of the Ahpo Xahil, sacked the temples and kidnapped a priest, acts that the Kaqchikel blamed on Pedro de Alvarado. Conquistador Bernal Díaz del Castillo recounted how in 1526 he returned to Iximche and spent the night in the "old city of Guatemala" together with Luis Marín and other members of Hernán Cortés's expedition to Honduras. He reported that the houses of the city were still in excellent condition; his account was the last description of the city while it was still inhabitable

At the time of the Spanish Conquest, the main Mam population was situated in Xinabahul (also spelled Chinabjul), now the city of Huehuetenango, but Zaculeu's fortifications led to its use as a refuge during the conquest. The refuge was attacked by Gonzalo de Alvarado y Contreras, brother of conquistador Pedro de Alvarado, in 1525, with 120 soldiers, and some 2,000 Mexican and K'iche' allies. The city was defended by Kayb'il B'alam commanding some 5,000 people (the chronicles are not clear if this is the number of soldiers or the total population of Zaculeu).

After a siege lasting several months the Mam were reduced to starvation. Kayb'il B'alam finally surrendered the city to the Spanish in October 1525. When the Spanish entered the city of Zaculeu they found 1,800 dead Indians, with the survivors eating the corpses of the dead.

By 1537 the area immediately north of the new colony of Guatemala was being referred to as the Tierra de Guerra ("Land of War"). Paradoxically, it was simultaneously known as Verapaz ("True Peace"). The Land of War described an area that was undergoing conquest; it was a region of dense forest that was difficult for the Spanish to penetrate militarily.

Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas arrived in the colony of Guatemala in 1537 and immediately campaigned to replace violent military conquest with peaceful missionary work. Las Casas offered to achieve the conquest of the Land of War through the preaching of the Catholic faith. It was the Dominicans who promoted the use of the name Verapaz instead of the Land of War.

In 1695 the colonial authorities decided to connect the province of Guatemala with Yucatán, and Guatemalan soldiers conquered a number of Ch'ol communities, the most important being Sakb'ajlan on the Lacantún River in eastern Chiapas, now in Mexico, which was renamed as Nuestra Señora de Dolores, or Dolores del Lakandon.

Martín de Ursúa arrived on the western shore of lake Petén Itzá with his soldiers in February 1697, and once there built a galeota, a large and heavily armed oar-powered attack boat. The Itza capital fell in a bloody waterborne assault on 13 March 1697. The Spanish bombardment caused heavy loss of life on the island; many Itza Maya who fled to swim across the lake were killed in the water. Catholic priests from Yucatán founded several mission towns around Lake Petén Itzá in 1702–1703.

Account of the Things of Yucatan (Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán)

A controversial figure in the history of the Christianization of central America was the friar Diego de Landa is at once reviled for his cruelty and for his destruction of invaluable historic materials about Maya culture and valued for his personal contributions to the study of the same. Landa’s Relación De Las Cosas De Yucatán is about as complete a treatment of Mayan religion as we are likely to ever have.

Allen Wells calls his work an “ethnographic masterpiece”, while William J. Folan, Laraine A. Fletcher and Ellen R. Kintz have written that Landa‘s account of Maya social organization and towns before conquest is a “gem.” Landa’s writings are our main contemporary source for Mayan history,without which our collective knowledge of Mayan ethnology would be devastatingly small. While Landa might have exaggerated some claims to justify his actions to his accusers, his intimate contact with natives and all around accuracy in other fields heavily implies his version of events has at least some truth in it.

Ironically, historian John F Chuchiak IV has suggested that the result of Landa's fervor to exterminate the traditional Maya religion in fact had the opposite effect and is partially the reason why Maya religion is still alive today in the Yucatán. He argues that Landa's excesses caused the secular authorities to remove the Franciscans' right to take disciplinary measures against idolaters while still leaving the Maya under the care of the Franciscans' cathechization. Chuchiak suggests that the revocation of the Franciscans' "rights" to administer punishments to idolaters was an important factor in the survival of Maya religion to this day.

Landa's Relación de las cosas de Yucatán also created a valuable record of the Mayan writing system, which despite its inaccuracies was later to prove instrumental in the later decipherment of the writing system.

In 1571 Landa was appointed Bishop of Yucatan and he took the seat in 1573. Landa's period as Bishop was marked by continued campaigns of extirpation of idolatry among the Maya and he continued attracting opposition from secular authorities who found his methods excessive.

After hearing of Roman Catholic Maya who continued to practice idol worship, he ordered an Inquisition in Mani ending with a ceremony called auto-da-fé. During the ceremony on July 12, 1562, at least twenty seven Maya codices and approximately 5,000 Maya cult images were burned. These actions earned Landa a controversial place in the history of the Christianization of the Americas.

This caused long conflict between the ecclesiastical judiciary system of de Landa and the Governors of Yucatán. Landa's Inquisition showered a level of physical abuse upon the indigenous Maya that was viewed as excessive even by other members of the church such as his predecessor as Bishop, Francisco de Toral.

Landa claims he had discovered evidence of human sacrifice and other idolatrous practices while rooting out native idolatry.

Landa was remarkable in that he was willing to go where no others would. He entered lands only recently conquered where native resentment of Spaniards was still very intense. Armed with nothing but the conviction to learn as much of native culture as he could, so that it would be easier for him to destroy it in the future, Landa formulated an intimate contact with natives. Natives placed him in such an esteemed position they were willing to show him some of their sacred writings that had been transcribed on deerskin books. To Landa and the other Franciscan friars, the very existence of these Mayan codices was proof of diabolical practices. In references to these books, Landa has said:

"We found a large number of books in these characters and, as they contained nothing in which were not to be seen as superstition and lies of the devil, we burned them all, which they (the Maya) regretted to an amazing degree, and which caused them much affliction."

Landa himself was never in doubt of the necessity of his inquisition. Whether magic and idolatry were being practiced or not, there can be little doubt Landa was “possessed” by fantasies of demonic power in a new land. Landa, like most Franciscans of the time, subscribed to millenarian ideas, which demanded the mass conversion of as many souls as possible before the turn of the century. Eliminating evil and pagan practices, Landa believed, would usher the Second Coming of Christ that much sooner.

Convinced that the Mayan spiritual traditions were the work of the devil, in July 1562, Landa burned five thousand native religious images and at least twenty-seven painted books filled with hieroglyph-like images.

Bishop Francisco de Toral finally stopped Landa's inquisition and sent him back to Spain, where, in 1564, he was tried for his excesses. He was eventually absolved of any misdeeds. As he waited for his case to be resolved, Landa wrote Relacion de las Cosas de Yucatan, now considered an authority on Mayan customs and language. The book would not be published for another three hundred years, but in the 20th century, Landa's work provided a valuable record and important clues for modern day scholars trying to decipher Mayan writing. After Toral's death, Landa was sent back to the New World in 1573 and was ordained Bishop of the Yucatan, a position he held until his death at age 54.

The process of conversion was described by Landa:

"Que los vicios de los indios eran idolatrías y repudios y borracheras públicas y vender y comprar esclavos; y que por apartarlos de estas cosas vinieron a aborrecer a los frailes; pero que entre los españoles los que más fatigaron a los religiosos, aunque encubiertamente, fueron los sacerdotes mayas, como gente que había perdido su oficio y los provechos de él

...

Que la manera que se tuvo para adoctrinar a los indios fue recoger a los hijos pequeños de los señores y gente más principal, poniéndolos en torno de los monasterios en casas que cada pueblo hacía para los suyos, donde estaban juntos todos los de cada lugar, cuyos padres y parientes les traían de comer; y con estos niños se recogían los que venían a la doctrina, y con tal frecuentación muchos, con devoción, pidieron el bautismo; y estos niños, después de enseñados, tenían cuidado de avisar a los frailes de las idolatrías y borracheras y rompían los ídolos aunque fuesen de sus padres, y exhortaban a las repudiadas; y a los huérfanos, si los hacían esclavos (los encomenderos o los mismos indios, decían) que se quejasen a los frailes y aunque fueron amenazados por los suyos, no por eso cesaban, antes respondían que les hacían honra pues era por el bien de sus almas

...

Que estando esta gente instruída en la religión y los mozos aprovechados, como dijimos, fueron pervertidos por los sacerdotes mayas que en su idolatría tenían y por los señores, y tornaron a idolatrar y hacer sacrificios no sólo de sahumerios sino de sangre humana, sobre lo cual los frailes hicieron inquisición y pidieron la ayuda del alcalde mayor prendiendo a muchos y haciéndoles procesos; y se celebró un auto (de fe) en que se pusieron muchos cadalsos encorozados. (Algunos indios fueron) azotados y trasquilados y algunos ensambenitados por algún tiempo; y otros, de tristeza, engañados por el demonio, se ahorcaron, y en común mostraron todos mucho arrepentimiento y voluntad de ser buenos cristianos

...

La pena del homicida aunque fuese casual, era morir por insidias de los parientes, o si no, pagar el muerto. El hurto pagaban y castigaban aunque fuese pequeño, con hacer esclavos y por eso hacian tantos esclavos, principalmente en tiempo de hambre, y por eso fue que nosotros los frailes tanto trabajamos en el bautismo: para que les diesen libertad.

....

Las mujeres son cortas en sus razonamientos y no acostumbran a negociar por sí (mismas), especialmente si son pobres, y por eso los señores se mofaban de los frailes que daban oído a pobres y ricos sin distinción.

"

The tense relation between friars and conquistadores was never really easy, as Landa described on his tale:

"Que los españoles tomaban pesar de ver que los frailes hiciesen monasterios y ahuyentaban a los hijos de los indios de sus repartimientos, para que no viniesen a la doctrina; y quemaron dos veces el monasterio de Valladolid con su iglesia, que era de madera y paja; tanto que fue necesario a los frailes irse a vivir entre los indios...

...

Que los frailes viendo este peligro enviaron al muy singular juez Cerrato, Presidente de Guatemala, un religioso que le diese cuenta de lo que pasaba, y visto el desorden y mala cristiandad de los españoles que se llevaban absolutamente los tributos y cuanto podían sin orden del rey (y obligaban a los indios) al servicio personal en todo género de trabajo, hasta alquilarlos para llevar cargas, proveyó cierta tasación, harto larga aunque pasadera, en que señalaba qué cosas eran del indio después de pagado el tributo a su encomendero, y que no fuese todo absolutamente del español. (Los encomenderos) suplicaron de esto y con temor de la tasa sacaban a los indios más que hasta allí, y entonces los frailes tornaron a la Audiencia y reclamaron en España e hicieron tanto que la Audiencia de Guatemala envió a un Oidor, el cual tasó la tierra y quitó el servicio personal e hizo casar a algunos, quitándoles las casas que tenían llenas de mujeres.

....

Que los indios recibían pesadamente el yugo de la servidumbre, mas los españoles tenían bien repartidos los pueblos que abrazaban la tierra, aunque no faltaba entre los indios quien los alterase, sobre lo cual se hicieron castigos muy crueles que fueron causa de que apocase la gente. Quemaron vivos a algunos principales de la provincia de Cupul y ahorcaron a otros. Hízose información contra los de Yobain, pueblo de los Cheles, y prendieron a la gente principal y, en cepos, la metieron en una casa a la que prendieron fuego abrasándola viva con la mayor inhumanidad del mundo, y dice este Diego de Landa que él vio un gran árbol cerca del pueblo en el cual un capitán ahorcó muchas mujeres indias en sus ramas y de los pies de ellas a los niños, sus hijos. Y en este mismo pueblo y en otro que se dice Verey, a dos leguas de él, ahorcaron a dos indias, una doncella y la otra recién casada, no porque tuvieran culpa sino porque eran muy hermosas y temían que se revolviera el real de los españoles sobre ellas y para que mirasen los indios que a los españoles no les importaban las mujeres; de estas dos hay mucha memoria entre indios y españoles por su gran hermosura y por la crueldad con que las mataron.

...

Que se alteraron los indios de la provincia de Cochua y Chectemal y los españoles los apaciguaron de tal manera que, siendo esas dos provincial las más pobladas y llenas de gente, quedaron las más desventuradas de toda aquella tierra. Hicieron (en los indios) crueldades inauditas (pues les) cortaron narices, brazos y piernas, y a las mujeres los pechos y las echaban en lagunas hondas con calabazas atadas a los pies; daban estocadas a los niños porque no andaban tanto como las madres, y si los llevaban en colleras y enfermaban, o no andaban tanto como los otros, cortábanles las cabezas por no pararse a soltarlos. Y trajeron gran número de mujeres y hombres cautivos para su servicio con semejantes tratamientos. Se afirma que don Francisco de Montejo no hizo ninguna de estas crueldades ni se halló en ellas, antes bien le parecieron muy mal, pero que no pudo (evitarlas).

...

por otra parte tenían razón los indios al defender su libertad y confiar en los capitanes muy valientes que tenían para entre ellos y pensaban que así serían contra los españoles.

"

Maya Architecture

At the heart of the Maya city existed the large plazas surrounded by their most valued governmental and religious buildings such as the royal acropolis, great pyramid temples and occasionally ballcourts. Though city layouts evolved as nature dictated, careful attention was placed on the directional orientation of temples and observatories so that they were constructed in accordance with Maya interpretation of the orbits of the stars.

Often the most important religious temples sat atop the towering Maya pyramids, believed to be the closest place to the heavens.

Landa wrote:

"Si Yucatán hubiere de cobrar nombre y reputación con muchedumbre, grandeza y hermosura de edificios como lo han alcanzado otras partes de las Indias, con oro, plata y riquezas, ella hubiera extendidose tanto como el Perú y la Nueva España, porque es así en esto de edificios y muchedumbre de ellos, la más señalada cosa de cuantas hasta hoy en las Indias se han descubierto, porque son tantos las partes donde los hay y tan bien edificados de cantería....

...En esta tierra no se ha hallado hasta ahora ningún género de metal que ella de suyo tenga, y espanta (que) no habiendo con qué, se hayan labrado tantos edificios porque no dan los indios razón de las herramientas con que se labraron"

Maya Art

The lay-out of the Maya towns and cities, and more particularly of the ceremonial centers where the royal families and courtiers resided, is characterized by the rhythm of immense horizontal stucco floors of plazas often located at various levels, connected by broad and often steep stairs, and surmounted by temple pyramids.

A common form of Maya stone sculpture was the stela. These were large, elongated stone slabs covered with carvings, often with round altars in front. Typical of the Classical period, most of them depict the rulers of the cities they were located in, often disguised as gods. The stelae almost always contain hieroglyphic texts, which have been critical to determining the significance and history of Maya sites.

Maya art of their Classic Era (c. 250 to 900 CE) is of a high level of aesthetic and artisanal sophistication. The carvings and the reliefs made of stucco at Palenque and the statuary of Copán, show a grace and accurate observation of the human form that reminded early archaeologists of Classical civilizations of the Old World, hence the name bestowed on this era. We have only hints of the advanced painting of the classic Maya; mostly what has survived are funerary pottery and other Maya ceramics, and a building at Bonampak holds ancient murals that survived by chance.

The Maya writing system (often called hieroglyphs from a superficial resemblance to the Ancient Egyptian writing) was a combination of phonetic symbols and logograms. It is most often classified as a logographic or (more properly) a logosyllabic writing system, in which syllabic signs play a significant role. It is the only writing system of the Pre-Columbian New World which is known to represent the spoken language of its community. In total, the script has more than a thousand different glyphs, although a few are variations of the same sign or meaning, and many appear only rarely or are confined to particular localities. At any one time, no more than around 500 glyphs were in use, some 200 of which (including variations) had a phonetic or syllabic interpretation.

At a rough estimate, in excess of 10,000 individual texts have so far been recovered, mostly inscribed on stone monuments, lintels, stelae and ceramic pottery. The Maya also produced texts painted on a form of paper manufactured from processed tree-bark, in particular from several species of strangler fig trees such as Ficus cotinifolia and Ficus padifolia. The inscriptions on the stelae mainly record the dynasties and wars of the sites' rulers. Also of note are the inscriptions that reveal information about the lives of ancient Maya women. Much of the remainder of Maya hieroglyphics has been found on funeral pottery, most of which describes the afterlife.

Shortly after the conquest, all of the codices which could be found were ordered to be burnt and destroyed by zealous Spanish priests, notably Bishop Diego de Landa. Fr. Bartolomé de las Casas lamented that when found, such books were destroyed:

"These books were seen by our clergy, and even I saw part of those that were burned by the monks, apparently because they thought [they] might harm the Indians in matters concerning religion, since at that time they were at the beginning of their conversion."

Only three reasonably intact examples of Maya codices are known to have survived through to the present day. These are now known as the Madrid, Dresden, and Paris codices. A few pages survive from a fourth, the Grolier codex, whose authenticity is sometimes disputed, but mostly is held to be genuine.

Scribes held a prominent position in Maya courts. Maya art often depicts rulers with trappings indicating they were scribes or at least able to write, such as having pen bundles in their headdresses. Additionally, many rulers have been found in conjunction with writing tools such as shell or clay inkpots. Although the number of logograms and syllabic symbols required to fully write the language numbered in the hundreds, literacy was not necessarily widespread beyond the elite classes.

Madrid codice: This codex was likely written after Spanish arrival, and was the result of hastily absorbed imagery and text from several sources. It is in the Museo de América in Madrid, Spain, where it may have been sent back to the Royal Court by Hernán Cortés. There are 112 pages, which got split up into two separate sections, known as the Troano Codex and the Cortesianus Codex. These were re-united in 1888. This Codex's provenance has been suggested to be Tayasal, the last Maya city to be conquered in 1697.

The Dresden Codex (Codex Dresdensis): It is held in the Sächsische Landesbibliothek (SLUB), the state library in Dresden, Germany. It is the most elaborate of the codices, and also a highly important work of art. Many sections are ritualistic (including so-called 'almanacs'), others are of an astrological nature (eclipses, the Venus cycles). The codex is written on a long sheet of paper that is 'screen-folded' to make a book of 39 leaves, written on both sides. It was probably written before the Spanish conquest, experts agree today, that originally came from Chichen Itza during the post-classical Maya period, in 1250 A. C.. Somehow it made its way to Europe and was bought by the royal library of the court of Saxony in Dresden in 1739. The only exact replica, including the huun, made by a German artist is displayed at the Museo Nacional de Arqueología in Guatemala City, since October, 2007. The Dresden Codex contains astronomical tables of outstanding accuracy. It is most famous for its Lunar Series and Venus table. The lunar series has intervals correlating with eclipses. The Venus Table correlates with the apparent movements of the planet. The codex also contains almanacs, astronomical and astrological tables, and ritual schedules. There are six pages in the Dresden Codex devoted to the accurate calculation of the location of Venus. The Maya were able to achieve such accuracy by careful observation over many centuries. The Venus cycle was especially important because the Maya believed it was associated with war and used it to divine appropriate times (electional astrology) for coronations and war. Venus was often referred to as both "The Morning Star" and "The Evening Star" because of its visibility during both times. Maya rulers planned for wars to begin when Venus rose. The Maya may have also tracked the movements of other planets, including Mars, Mercury, and Jupiter.

The Paris Codex (also or formerly the Codex Peresianus) contains prophecies for tuns and katuns (see Maya Calendar), as well as a Maya zodiac, and is thus, in both respects, akin to the Books of Chilam Balam. The codex first appeared in 1832 as an acquisition of France's Bibliothèque Impériale (later the Bibliothèque Nationale, or National Library) in Paris. Three years later the first reproduction drawing of it was prepared for Lord Kingsborough, by his Lombardian artist Agostino Aglio. The original drawing is now lost, but a copy survives among some of Kingsborough's unpublished proof sheets, held in collection at the Newberry Library, Chicago. Although occasionally referred to over the next quarter-century, its permanent "rediscovery" is attributed to the French orientalist León de Rosny, who in 1859 recovered the codex from a basket of old papers sequestered in a chimney corner at the Bibliothèque Nationale where it had lain discarded and apparently forgotten. As a result, it is in very poor condition. It was found wrapped in a paper with the word Pérez written on it, possibly a reference to the Jose Pérez who had published two brief descriptions of the then-anonymous codex in 1859. De Rosny initially gave it the name Codex Peresianus ("Codex Pérez") after its identifying wrapper, but in due course the codex would be more generally known as the Paris Codex. De Rosny published a facsimile edition of the codex in 1864. It remains in the possession of the Bibliothèque Nationale.

Other sources about the Mayas from the early-colonial (16th-century) period are for example the Popol Vuh, the Ritual of the Bacabs, and (at least in part) the various Chilam Balam books.

- Popol Vuh is a corpus of mytho-historical narratives of the Post Classic K'iche' kingdom in Guatemala's western highlands. The title translates as "Book of the Community," "Book of Counsel," or more literally as "Book of the People." Popol Vuh's prominent features are its creation myth, its diluvian suggestion, its epic tales of the Hero Twins Hunahpú and Xbalanqué, and its genealogies. The myth begins with the exploits of anthropomorphic ancestors and concludes with a regnal genealogy, perhaps as an assertion of divine right rule. Popol Vuh's fortuitous survival is attributable to the 18th century Dominican friar Francisco Ximénez.

In 1701, Father Ximénez came to Santo Tomás Chichicastenango (also known as Santo Tomás Chuilá). This town was in the Quiché territory and therefore is probably where Fr. Ximénez first redacted the mythistory. Ximénez transcribed and translated the manuscript in parallel K'iche' and Spanish columns (the K'iche' having been represented phonetically with Latin and Parra characters). In or around 1714, Ximénez incorporated the Spanish content in book one, chapters 2-21 of his Historia de la provincia de San Vicente de Chiapa y Guatemala de la orden de predicadores. Ximénez's manuscripts remained posthumously in the possession of the Dominican Order until General Francisco Morazán expelled the clerics from Guatemala in 1829–30 whereupon the Order's documents passed largely to the Universidad de San Carlos.

From 1852 to 1855, Moritz Wagner and Carl Scherzer traveled to Central America, arriving in Guatemala City in early May 1854. Scherzer found Ximénez's writings in the university library, noting that there was one particular item "del mayor interes" ('of greater interest'). With assistance from the Guatemalan historian and archivist Juan Gavarrete, Scherzer copied (or had a copy made) of the Spanish content from the last half of the manuscript, which he published upon his return to Europe. In 1855, French Abbot Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg also found Ximénez's writings in the university library. However, whereas Scherzer copied the manuscript, Brasseur apparently "absconded" with the university's volume and took it back to France. After Brasseur's death in 1874, the Mexico-Guatémalienne collection containing Popol Vuh passed to Alphonse Pinart through whom it was sold to Edward E. Ayer. In 1897, Ayer decided to donate his 17,000 pieces to The Newberry Library, a project that tarried until 1911. Father Ximénez's transcription-translation of "Popol Vuh" was among Ayer's donated items. Father Ximénez's manuscript sank into obscurity until Adrián Recinos (re)discovered it at The Newberry (in Chicago) in 1941.

Contemporary archaeologists (first of all Michael D. Coe) have found depictions of characters and episodes from Popol Vuh on Maya ceramics and other art objects:

- The Maya Hero Twins are the central figures of a narrative included within the colonial K’iche’ document called Popol Vuh, and constituting the oldest Maya myth to have been preserved in its entirety. The Hero Twins were Xbalanque and Hunahpu (Modern K'iche': Xb‘alanke and Junajpu) who were ballplayers like their father and uncle, Hun Hunahpu and Vucub Hunahpu. Called Hunahpu and Xbalanque in the K’iche’ language, the Twins have also been identified in the art of the Classic Mayas (200-900 AD). The Twin motif recurs in many native American mythologies; the Mayan Twins in particular could be considered as mythical ancestors to the Mayan ruling lineages. Summoned to Xibalba by the Lords of the Underworld, the father and uncle were defeated and sacrificed. Hun-Hunahpu's head was suspended in a trophy tree and changed to a calabash. Its spittle (i.e., the juice of the calabash) impregnated a daughter of one of the lords of Xibalba, Xquic. She fled the underworld and conceived the Twins. The two sons were engendered (by the seed of the dead father). The pregnant mother fled from Xibalba. The sons - or 'Twins' - grew up to avenge their father, and after many trials, finally defeated the lords of the Underworld in the ballgame:

Every day the twins played ball against the gods, just managing to hold their own. A loss would cost them their lives. Each night they faced other dangers in the houses where they slept: the Dark House, Razor House, Jaguar House. They escaped with cunning and the help of forest creatures—until the night in the Bat House, where snatcher bats flew. The boys slept inside the tubes of their blowguns for protection, but Hunahpú stuck his head out too soon and was decapitated. The next day, the gods used Hunahpú’s head in place of the ball. Xbalanqué was able to trick them, however, and reunite his brother’s head and body. In the end, it was the gods who lost that game.